The Ontology of Open Mouths: The Scream and the Swallowing

In his studies of the grotesque and carnivalesque (what we might consider a theoretical precedent for queer theories of camp), Russian philosopher Mikhail Bakhtin identifies the mouth as “the most important of all human features for the grotesque.” As he puts it, “the grotesque face is actually reduced to the gaping mouth; the other features … only a frame encasing this wide open bodily abyss.”

Indeed, the mouth agape is a many-faced thing: among the most prevalent motifs of the horror genre on film, noteworthy also in literature, other modes of visual art, mythology, and folklore. Contained within its many significations — a spectrum that runs from terror to wonder to song — are the grand preoccupations of the human and nonhuman condition alike.

Julia Kristeva defined abjection, the experience of fear, distaste, or repulsion as a violation or trespass of prescribed borders — the perspective from which most approaches to the genre derive. This is, like all things, however, a matter of perception, and in the case of horror films, many suggest an overarching preoccupation with not just trespass, but what I call the Swallowing: the occasion in horror reflecting an explicit fear of being consumed.

In its most literal sense, the Swallowing appears in eco-horror like Jaws, The Birds, The Fog, Frogs, and The Descent which all see elements of the natural world threaten humanity’s perceived sovereignty in the form of some devouring menace. It’s also seen in many of our most popular cultural monsters — vampires, werewolves, zombies, cannibals, succubi — to whom the human body is made meat for their monstrous appetites.

Psychic consumption takes the form of demon possession, all-manner of Body Snatchers-type narratives, characters who become “unhinged,” and, of course, the threat of brainwashing and cults. Even within haunted house movies, home and alien invasion plots, viral outbreaks which shatter society — these themes that perhaps most overtly reflect an essential fear of trespass — dually reveal how it’s not solely the gesture of trespass that we fear, but what we believe trespass to inherently indicate: consumption and dissolution.

Annihilation, thus, is located in the swallowing mouth; not just a hole, but a black hole.

If we understand the Swallowing as an umbrella term for these varied occurrences of devouring monsters while also accepting that monsters necessarily reflect the anxieties of the culture which created them, then what does the Swallowing reveal to us about the construction of Black monstrosity and where we locate and weaponize fear in our culture? Further, how might this monstrousness be reimagined as a vehicle for catharsis?

If someone were to ask me why 1992’s Candyman is not a Black Horror film (apart from the traditional reason which is that it was written and made by white people), I’d need only reference this image.

Though the film’s namesake, Candyman is explicitly not its emotional core. It’s Helen, the white anthropology student studying the urban legend, who is the subject and center of this movie, just as she’s the center of this shot. Her relationship to Cabrini-Green, the housing project he haunts (a decision which makes very little sense given his backstory), is essentially one of tourism and extraction.

The film’s not-so-subtle subtext stokes a specific and pathological preoccupation with Black men’s perceived desire for white women. The evidence of Candyman’s monstrosity is primarily located in his mouth, which, in other moments, teems with swarms of killer bees. In this case (and in this image), Black male desire represents the occasion of the Swallowing, echoing earlier appearances of coded (and not-so-coded) renderings of Black men as monstrous Others (King Kong, Creature from the Black Lagoon, Ingagi, Birth of a Nation).

Meanwhile, Rusty Cundieff’s Tales from the Hood 2 features a similarly composed shot in the first tale, Good Golly, to drastically different effect.

Cundieff has confirmed the doorway entering the Museum of Negrosity references the infamous Coon Chicken Inn restaurants. The implication being that, as the two girls at the center of the tale — Audrey, who is white, and Zoe, who’s Black — pass through the mouth of this caricature, they’ve left behind the world which pretends to be “color-blind” and entered a space where the evidence of racism and white supremacy is unignorable.

Collected in this museum are relics of anti-Black Americana; its mission, to refuse the sugar-coated, white-washed overhaul of this country’s history. Certain dynamics are already evident between the two girls, and the imbalance of influence is exacerbated when Audrey is thrilled to discover a doll of the controversial (read: racist) golliwog character she played with as a child. In all her entitlement, she insists on being able to purchase it, refusing to recognize its existence as a cursed object.

In this case, Blackness is still equated with a devouring force — something which, if acknowledged, would fundamentally necessitate reconsideration of the ways we relate to one another and the world. Here, the Swallowing is represented as that all-consuming shift in perspective, threatening only to those whose goal is revision and suppression.

Let’s, too, consider the scream, the other instance of open mouths most prevalent in horror. A physiological response to fear, yes. But it’s also something born of laughter, grief, ecstasy, or rage, all of which ultimately represent catharsis.

The complicating of these expressive, emotional boundaries is the lifeblood of any great horror climax. Recall Texas Chainsaw Massacre’s closing crescendo: the cacophony of Leatherface’s chainsaw, an extension of his bodily self, and Sally’s sustained screaming from the back of the pickup truck; the moment her screams of terror melt into jubilation.

While we may consider the scream a sonic experience, it’s a visual and imagined experience as well, and the image most relied upon within non-sonic mediums to address (read: project) suffering, anguish, and fear to a given form. Indeed, Edvard Munch’s painting, “The Scream” represents a key example.

Another would be Frederick Douglass’ description of his Aunt Hester’s screams as recalled in his Narrative of the Life of… and again in My Bondage, My Freedom; analysis of which accounts for the introductions to both Saidiya Hartman’s Scenes of Subjection: Terror, Slavery, and Self-Making in Nineteenth-Century America as well as Christina Sharpe’s Monstrous Intimacies: Making Post-Slavery Subjects.

Hartman’s approach is unique for its refusal to reproduce the text detailing the scene of astounding brutality to which Douglass first bears witness, and then forces us, his reader, to bear witness too in turn. Not unlike many perspectives regarding the spectacle (and propagation) of Black death shared across social media, Hartman’s argument, which Sharpe reproduces and builds on, roots itself in the belief that instead of “inciting indignation, too often [such accounts] immure us to pain by virtue of their familiarity.” Scholar, Zalika U. Ibaorimi further affirms this point, calling it “imperative to consider Hartman’s decision to not recount the violences of Aunt Hester, while also introducing her trauma.”

Despite its 1996 release, the original Scream is an overwhelmingly white film: the type of homogenization whose absences tell an unwitting story about white flight and the project of suburbia, something Robert Palmer considers in his 2011 essay, Scream 2 and the African American Element. Further consideration are the motives behind the film’s racial commentary, the decided focus of the sequel’s opening sequence with questionable success.

There are clear similarities between the Ghostface mask itself and Munch’s anguished subject, a trick mirror of sorts. Tension is effectively built through the sheer proliferation of masks onscreen and Maureen’s (Jada Pinkett-Smith) visible discomfort with their omnipresence, a very specific anxiety echoed in her inability to relax while surrounded by hooded figures.

After killing Phil (Omar Epps) in the bathroom, Ghostface stabs Maureen in the stomach just as Heather Graham is simultaneously stabbed onscreen, their screams sounding around each other. Bleeding and desperate, she stumbles through the audience, onto the stage, and looks out at the sea of white-faced masks, all of them the face of her killer, as the movie is projected over her body.

Of this scene, Ibaorimi writes, “as she screams from the pain, fear, and utter disgust of how invisible and visible she is to the white audience, she dies.” And at that very moment of collapse, of realization, Ghostface’s gaping mouth encases her, her demise having literally become the show.

Enormous pathos is granted to this scene, suggested by its very length and somewhat melodramatic treatment. It’s clear the audience is meant to be sad to see these characters die. Nevertheless, her death is sensationalized in a way that negates catharsis by simply reproducing the violence of the banal.

As Sharpe states:

We know that the repetition of such horror does not make the violence of everyday black subjection undeniable because, presented in its most spectacular form, [violence] does not confirm or confer humanity on the suffering black body, but all too often contributes to what Jesse Jackson calls…’an amazing tolerance for black pain…[a] great tolerance for black suffering and black marginalization.’

When Sidney (Neve Campbell) and Dewey (David Arquette) later discuss their murders, Sidney asks, “three hundred people watched? Nobody did anything?” Sheepishly, Dewey responds, “they thought it was a publicity stunt.”

Revealed in Hartman, Sharpe, and Ibaorimi’s analysis and its application to the film is the understanding that there has never been a lack of visibility for Black people’s, and, more specifically, Black women’s suffering (as Douglass and other abolitionist authors exemplified in the nineteenth century). What has and continues to persist is a lack of care. Reproducing violence does not provide catharsis from violence. It only reifies it.

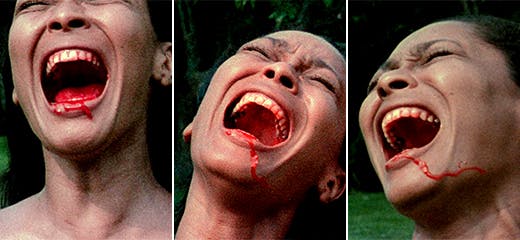

In contrast, we can look to Bill Gunn’s 1973 experimental film, Ganja and Hess. Though there are several occasions of the open mouth worthy of close examination in this film which uses vampirism (hunger) as a vehicle to explore several anxieties of Black life, I’d like to examine two specific shots — one representing the Swallowing, the other the scream.

Captured in this shot is what the poet Carl Phillips describes as “the zone of tragedy — transition”, “when the body surrenders to risk, that moment.” In the film, a disembodied choir sings “You’ve Got to Learn to Let it Go,” and Ganja becomes something new.

In her work of autotheory, Shadow Without Object, Katrin Hanusch writes of the symbology of the hole that it is “the absence of a boundary between two spaces touching each other … through which we expect thing to come or pass.” It represents “the hidden,” which she posits “both threatens and allures.”

Here, Ganja’s open mouth is a portal: the moment of transformation.

The below moment, too, is transitory, though of a different sort; concerned with the mortification and catharsis of self-realization.

With Ganja blood-sick in the aftermath of her new becoming, Hess brings a man, “a guest,” to dinner, essentially to be dinner. And as is typically the case with vampire narratives, biological hunger is overlayed with sexual desire. Part of what makes the catharsis of the scream so effective is Gunn’s willingness to take his time building tension so that, at the moment of the scream, it could successfully contain several degrees of satiation and release simultaneously.

Prior to their wedding and her transformation, Ganja recounts a “very decisive” day in her childhood: the moment she declared her own self “valuable,” embracing the “disease” projected to her Black femininity (and sexuality, in particular, which whiteness’ impact attempted to strip from her before she was even old enough to consider it for herself). She reveals how, on this day, she vowed to “take whatever steps had to be taken. But always take care of Ganja.”

In her lyric essay, The Black Catatonic Scream, Harmony Holiday notes how “For the African diaspora, the scream has been an emancipatory preoccupation.”

The reality of having fulfilled this promise to herself, combined with other condemned gratifications, appears to overwhelm and shatter Ganja. Indeed, neither she, nor Hess, nor their love is the same on the scream’s other side: that shift of gravity, a type of swallowing.

Holiday writes:

If you cannot describe what is happening to you yet, you are not complicit in making it real … The holds (patterns of human cargo) go quiet the way a child’s screams do when the tantrum is exhausted. No relief has come, and the body knows it needs to rest and roams the cosmos for the answers that no scream reveals.

It’s worth noting that the film does not end on this tragic sentiment (part of my personal love for the character). Ganja does take care of Ganja. She finds the answer to that scream in freeing herself of moral judgements prescribed by religion, white supremacy, and patriarchy.

The answer to the question, “what’s on the other side of the hole?” is always possibility. Always the future.

Lea Anderson is an independent horror scholar, critic, and poet, currently based just outside Los Angeles. Follow her on Twitter.