Horror’s Profound Empathy

I love horror. I love the sound of a hundred voices in a theater gasping in terror then letting out cathartic peals of laughter to relieve tension. I love listening to ghost stories with my kiddo outside in her tent. During the scary bits, she talks fast over the audio as a way to cope, and nothing brings me more joy. I love horror movies because that ball of worry that threatens to chew a hole in my stomach during the scariest bits mirrors how I experience anxiety. Taming those anxieties through controlled breathing or slowing down racing thoughts reminds me that I can do the same during real-world situations. I’m not alone in this; millions live with anxiety. What makes us unique is how we process and act on our symptoms. Horror affords people the opportunity to work through crippling worry that repeats itself like a needle stuck in a groove. It even gives us the chance to learn what scares people different than ourselves, who share different cultures, values, and experiences from our own.

What is it about horror as a genre that can lead to increased empathy for others? Over time, horror has transitioned between being a source of entertainment and a learning tool that teaches us about the privileges we take for granted. For a couple of hours, the character’s terror becomes our own, making space to engage with different backgrounds and experiences than our own. There are specific terrors I fail to consider in the real world; broken street lamps don’t give me pause; footsteps from behind me aren’t a reason to turn keys into a makeshift weapon; a minor traffic violation or accidentally bumping into someone in a store won’t lead to a gun pointed in my face. I have it easier than most.

In Horror Noire, author and UCLA professor Tananarive Due shares experiencing Get Out with a primarily white audience. She talks about Chris’ (Daniel Kaluuya) daring and violent getaway from his captors. She tells of the crowd rooting on each step towards his escape, and the eruption of celebration when he succeeds and the credits roll. Finally, the empathy Black audiences have been asked to feel for white characters has been reciprocated. What could be remedied through representation has remained too elusive for too long.

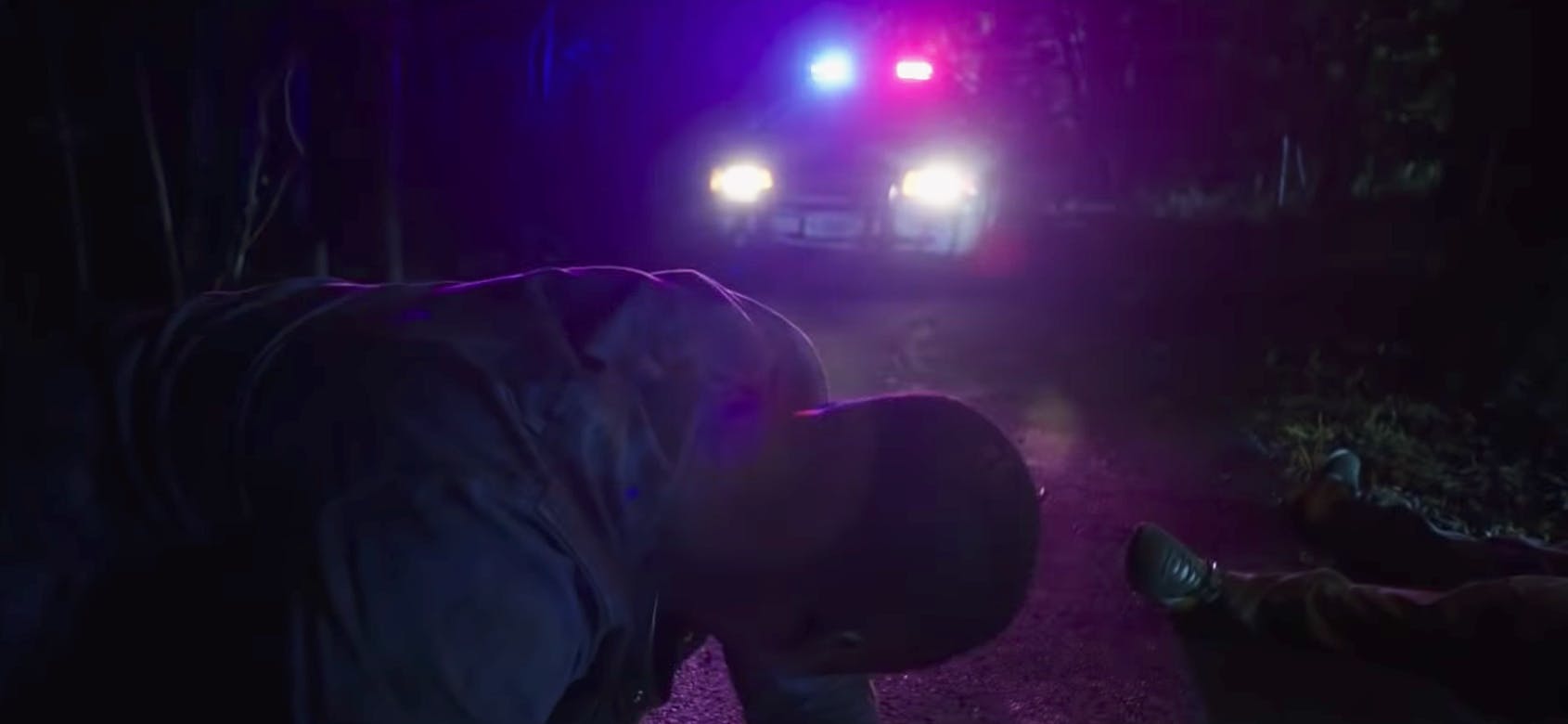

If you were one of the members of that raucous crowd, I have a question: Moments before Chris hops into Rod’s security vehicle, what did you feel? I bet the moment red and blue lights flashed across the screen the bottom dropped out of your stomach. We know how this scene plays out. We’re conditioned to expect tragedy. We’re holding our collective breath, only to have the air rush out in a whoosh of relief, followed by cheers and laughter.

Now is the time to transform that euphoria into hard work.

Empathy demands that we ask ourselves what we take for granted that sends others into a spiral of panic. It insists on digging even deeper and asking how we’ve contributed to that environment of hostility and what we can do to tear it down and rebuild it so it works for everybody.

At the same time, making room for Black voices, Brown voices, Queer voices, and those of other marginalized groups allows audiences an opportunity to see themselves reflected on screen or on the page. It reminds members of those communities that they don’t suffer alone, that their pain is real, and that their voices will not go unheard.

There will always be those that decry the mix of politics, culture, and horror as nothing more than a Soros-funded SJW plot to ruin entertainment. They’ll pine for times when politics weren’t so explicit, believing that John Carpenter made a popcorn flick about aliens instead of condemning Reagan-era greed and the political structure that demonized the poor and shoveled money into the hands of the wealthy (They Live). They’ll dismiss criticisms of underrepresentation, tokenism, and broad stereotypes that cater to the lowest common denominator as feeble attempts to score “woke points”, or bemoan that “everyone is just too sensitive nowadays.”

If you recognize yourself in these arguments, here’s some advice; it costs you nothing, not a single penny, to listen. Listening doesn’t mean crafting your rebuttal while the other person speaks; it leaves “whataboutisms” in the dustbin where they belong.

It means reflecting on what you’re hearing and what’s being asked of you. It means digging into exactly what it is about differing perspectives that makes you so uncomfortable. It means examining past actions and conversations for times you weren’t the “good guy” you profess to be. Having empathy means victims aren’t responsible for baring the details of their trauma at your feet so you can parse out the parts of their experiences you feel matter.

Of course you can appreciate works like Jennifer’s Body, The Babadook, the forthcoming Candyman, Revenge, Knife & Heart, Ganja & Hess, and many more as pure entertainment. Horror movies are fun. Twelve-year-old me watched Freddy’s Revenge scared out of his gourd only occasionally able to peer out from behind the sofa. He had zero clue about any of the subtext lurking just below the film’s surface.

If curiosity plateaus, then the real value of horror as an art form would be lost, along with the depth of riches it offers as a reward to those that want to dig deeper.

Mike Snoonian is the cohost of The Pod & the Pendulum podcast and the upcoming Psychoanalysis: A Horror Therapy Podcast. He is a trained mental health professional and works as a therapist and school adjustment counselor.